Process Makes Perfect: An Overview of Printmaking Techniques

/When you visit the Gallery, you’ll notice an array of fine art prints. Each represents a distinct printmaking technique with a fascinating, often complex, process. Here, we’ll provide a brief description of the main techniques you’ll see at the Gallery.

Etching

Etching is a form of intaglio printmaking, which includes any process where an image is engraved into a plate and the grooves hold the ink.

In etching, the primary plates used are polished copper or zinc. These are coated with acid-resistant wax or varnish on which the artist inscribes the image with a needle.

Next, the plate gets an acid bath, which eats through the areas where the artist carved through the acid-resistant layer. The image is then seared into the plate and ink can be applied for making prints.

Drypoint

Similar to etching, drypoint involves carving a design directly into a copper or zinc plate, skipping the acid-resistant layer and acid bath.

Ralph Pearson (1883-1958) - “Duran Chapel”, 1919, Etching, 4 ½ x 6 ¾ in.

Aquatint

Following the basic principles of etching, aquatint allows artists a greater range of tonal values and blending effects.

Instead of applying the wax-resistant varnish to the plate, powdered rosin is sprinkled across it then heated to adhere it to the surface. That rosin becomes the resistant layer once the plate is submerged in the acid bath.

Acid then “bites” into the plate at varying levels depending on the concentration of resin. This ability to control opacity of ink gave etchers more freedom and ultimately added more depth to their pieces.

Charles Capps (1898-1981) - “East of Santa Fe”, Ed. of 60, Aquatint, 7 x 9 in.

Woodblock/Woodcut

Originating in China and associated with the renowned Japanese Ukiyo-e artists, woodblock printing is one of the oldest printmaking techniques. The Diamant-Sutra, the first book produced using woodblock, was printed in China in 868—and the technique dates back further than that.

Woodblock is a form of relief printing, meaning the carved areas represent negative space. For multi-colored prints, artists use separate blocks, each carved specifically to show only that color. The print must be carefully lined up on each block to achieve the finished image.

In the European style, artists roll oil-based ink across the block(s), which is transferred to paper via printing press. The traditional Asian method uses water-based inks and rubbing to transfer the image, creating a watercolor-like effect.

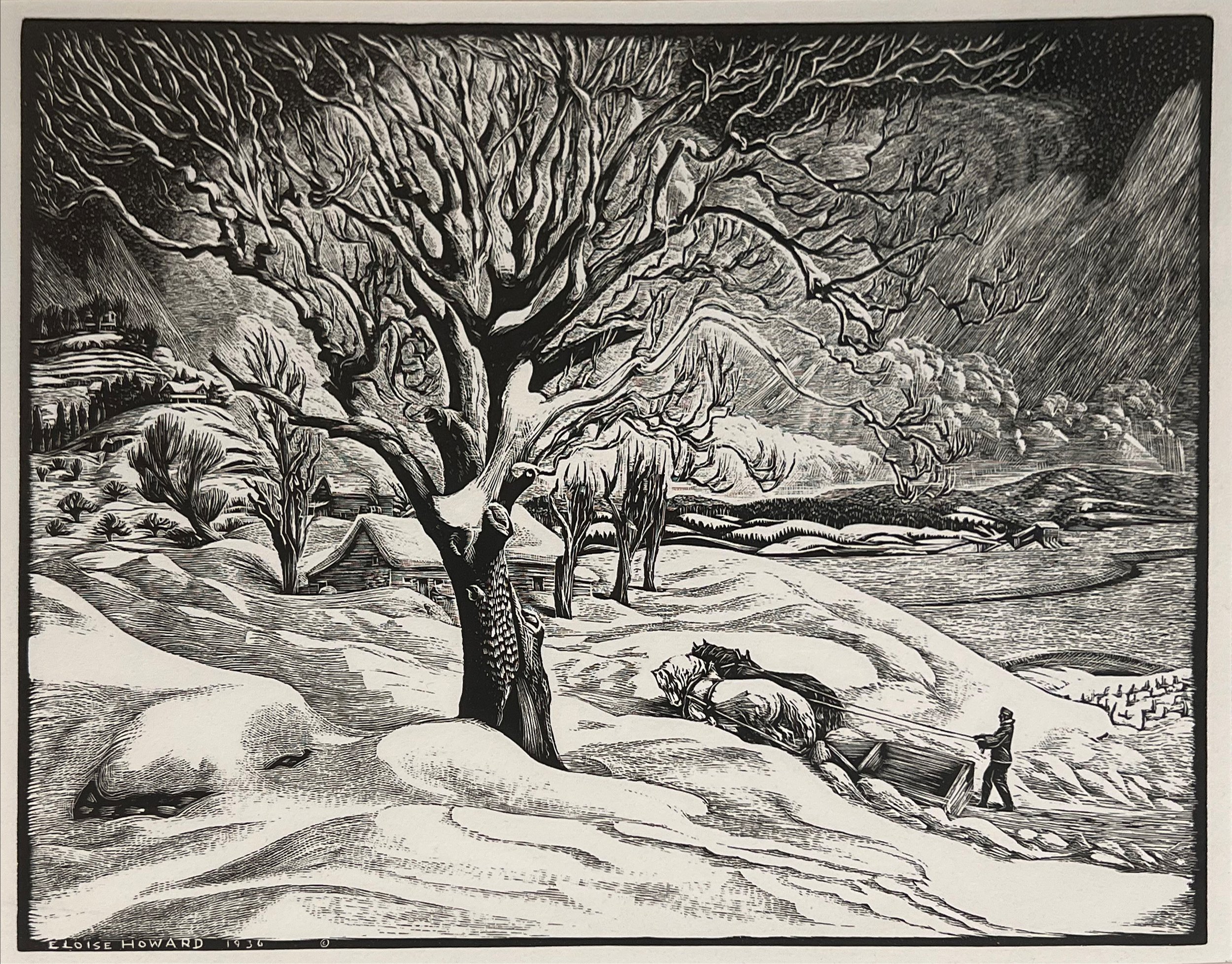

Eloise Howard (1889-1985) - “Opening the Road”, 1936, Ed. of 200, Woodblock Print, 10 x 12 in.

Artists creating woodblock prints often had Japanese master artisans carve the individual blocks. The seal(s) of the craftsman can be seen in the bottom right corner in the piece above.

Silkscreen/Serigraphy

The last technique we’ll cover is silkscreen or serigraphy, the term sometimes used when referring to the art form over other applications. It is widely used commercially as silkscreen can print on everything from clothing to plastic—even objects that aren’t flat—and produce virtually endless copies.

For both the fine art and commercial methods, the process involves frames of fine yet strong gauze through which ink is pressed with a squeegee. The initial design is drawn over the screen, which is entirely coated in glue. The glue is removed from the design, leaving glue (sometimes paper or film are used instead) covering the nonprinting parts, letting ink pass through the design.

Lithography

Starting with a flat, polished surface like a lithography stone (limestone) or metal plate, the artist draws directly onto it with a wax-based crayon or ink.

From there, the stone is coated with powdered rosin followed by powdered talc. Next comes a layer of gum arabic. This mixture creates a chemical reaction, affixing the drawing to the surface of the stone while ensuring ink won’t breach the negative space.

The original drawing is then wiped away using litholene, leaving a trace of the original. Asphaltum is then applied with a brush and allowed to dry, which forms the surface for printmaking.

Next, the stone is coated with water and a layer of oil-based ink. The final prints are made using a dampened sheet of paper laid on top of the stone. A board called a tympan is set on top of the paper and sometimes padded with newspaper as the bar of the flatbed press ensures even distribution of the ink.

For multicolored lithographs, many stones are needed. Each would have only the individual color on it requiring the paper to be painstakingly aligned each time.

Lithography stone belonging to Nicolai Fechin. (Not for sale)

Ward Lockwood (1894-1963) - “Untitled (Making Adobe Bricks)”, Ed. of 12, Lithograph, 10 ½ x 14 ¼ in.

These pieces and many more are available at Nedra Matteucci Galleries in Santa Fe. For pricing and more information, call the Gallery at (505) 982-4631 or email inquiry@matteucci.com